![]() To understand what is myeloma and what are its symptoms, it helps to look first at the bone marrow and the way it works normally.

To understand what is myeloma and what are its symptoms, it helps to look first at the bone marrow and the way it works normally.

The outside of bones is very hard and dense, but the inner layer of larger bones, like the spine, skull, pelvis, shoulders and the heads of long bones, are made of flexible, spongy bone marrow. These larger bones are usually affected by the symptoms of myeloma; the small bones of the hands and feet are not normally affected. Because it affects many parts of the body, the condition is also known as multiple myeloma.

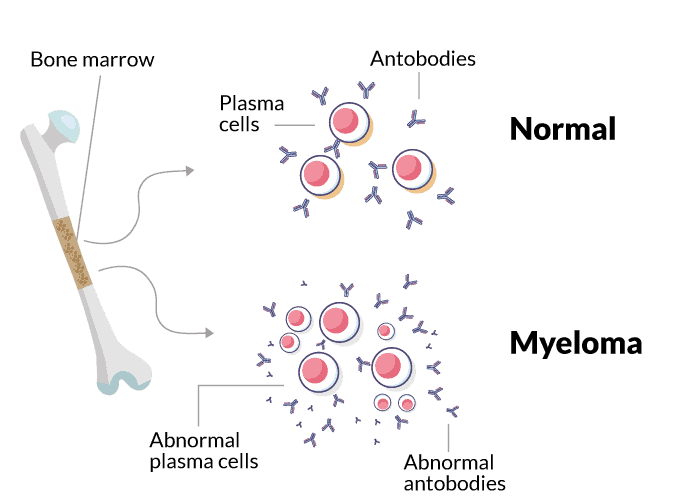

Bone marrow is the production site for red and white blood cells and blood platelets – the three main types of cells that circulate in the blood. One type of white blood cell is the plasma cell. These cells produce antibodies (immunoglobulins) to fight infection and are an important component of the body’s immune system.

Antibodies are made up of two different kinds of proteins, called heavy chains (which are larger) and light chains (smaller). An antibody has a Y-shaped structure made up of two identical heavy chains and two identical light chains. There are five different types of heavy chains called G, A, M, D or E; they are usually described as IgG (standing for immunoglobulin G), IgA, IgM, IgD or IgE. Your myeloma will be described by the type of heavy chain detected; IgG myeloma is the most common. The light chains are either κ (kappa) or λ (lambda).

Myeloma is rare, accounting for 1% of all cancers and 15% of blood cancers, but it is the second most common blood cancer after non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. In Europe about 50,918 people were diagnosed with myeloma in 2020. Myeloma can affect adults of any age, but it is much more common in people aged over 60 years (with the average age of 70 at diagnosis), and in men rather than women. Only 2% of cases of myeloma are diagnosed in people under the age of 40.

Myeloma is caused by damage to DNA during development of the plasma cells in the bone marrow, causing them to divide uncontrollably. The abnormal plasma cells, or myeloma cells, release only one type of antibody, known as paraprotein or M-protein, which is also made up of heavy and light chains but has no useful function. Sometimes groups of myeloma cells can accumulate in the form of a tumour in soft tissues outside the bone marrow, and these are known as plasmacytomas.

The build-up of myeloma cells in the bone marrow prevents normal blood cells from being produced. The build-up of myeloma cells and the presence of paraprotein in the blood and urine cause most of the symptoms of myeloma. Measuring the amount of paraprotein present in the blood is useful in diagnosing myeloma or monitoring its progress.

In about 20% of people with myeloma, the abnormal plasma cells only produce the ‘light chain’ part of the paraprotein structure, and this condition is known as light chain myeloma, or Bence Jones myeloma. In about 1% of myeloma patients, no paraprotein or light chains are produced, and this is non-secretory myeloma.

Myeloma may cause symptoms that need treatment. When myeloma doesn’t cause symptoms, we call it asymptomatic, indolent, or smouldering myeloma. Smouldering myeloma may or may not be treated depending on the risk of progression to symptomatic myeloma.

The goal of treating myeloma is to achieve a good quality response, so the patient can have a long period of remission. Myeloma may recur several times during the patient’s life, in which case it may be necessary to treat it again using different drug combinations.

For most people with myeloma, the exact causes are not clear but are thought to be a combination of genetic and environmental factors. Some of the factors that may be implicated are viruses, radiation, exposure to specific chemicals and a generally weakened immune system.

Myeloma is slightly more likely to occur if a family member also has it, which suggests there may be an inherited susceptibility, although this has yet to be proven. However, other environmental factors must also be present before myeloma will develop.

Although the exact cause of myeloma is not known, quite a lot is known about the factors which are linked with an increased risk of myeloma, although many patients are not affected by any of these:

- Age, gender and race: Myeloma is more common with increasing age. It is about twice as common in people of African origin than in white or Asian people, and three men are diagnosed with myeloma for every two women

- Family history: People with a parent, sibling or child who has myeloma are up to twice as likely to develop myeloma as those who have not

- Obesity is considered a risk factor for myeloma

- Exposure to toxic chemicals and radiation

- Autoimmune disorders, e.g., rheumatoid arthritis and multiple sclerosis

- Viral infections, e.g., hepatitis, HIV and herpes

What are the symptoms?

Myeloma is a complex cancer with both physical and emotional effects. Not everyone has all the symptoms, but the following are the most common physical effects. The emotions and feelings that can arise, starting from diagnosis, are discussed in section 3.1 and Chapter 6.

- Pain: Most myeloma patients will unfortunately suffer a dull, aching pain at some stage due to the abnormal activity in the bone marrow. Myeloma bone disease most often affects the middle or lower back, the rib cage or the hips, and movement can be painful.

- Anaemia: The reduction in the number of red blood cells, which carry oxygen throughout the body, results in anaemia. This can cause fatigue, weakness or shortness of breath, and can result either from the myeloma or as a side-effect of treatment.

- Fatigue: overwhelming tiredness is very common. It is often linked with anaemia rather than the myeloma itself; or it can be a side-effect of treatment. Fatigue can affect your ability to work, or limit how well you are able to move about

- Fractures: bones are more likely to break in people with myeloma; particularly the spinal vertebrae and ribs.

- Recurring infection: myeloma patients have a greater risk of infection, because their immune system is not working properly and there is a lower-than-normal level of white blood cells.

- Unexplained bruising: due to a low level of blood platelets; also meaning you may have a higher risk of bleeding.

- High blood calcium (hypercalcaemia): calcium can be released into the blood as bone is broken down, therefore raising the blood calcium level higher than normal. This can cause thirst, nausea, vomiting, confusion or constipation.

Stages and types of myeloma

It is now recognised that people who develop myeloma have previously had (although not necessarily been diagnosed with) a condition called monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS). This is typically seen in people with a raised level of paraprotein, but no other symptoms, like bone disease or a higher than 10% level of abnormal plasma cells in the bone marrow. Even if there are up to 30% of abnormal plasma cells (that is, a higher level than in MGUS), this level can rise very slowly and still show no symptoms; a condition known as smouldering myeloma.

Neither MGUS nor most smouldering myeloma patients need treatment, but patients will be monitored at least once a year. Not all MGUS patients go on to develop myeloma; the cause of the change to myeloma is not yet understood but is probably genetic. On the other hand, smouldering myeloma patients will eventually progress to symptomatic myeloma.

Prognosis

Even though there is still no cure for myeloma, the new drugs developed in the last decade are improving myeloma survival faster than for any other kind of cancer.

Myeloma is affected by many different factors, so it is impossible to predict how long an individual person is likely to live. This will depend on the exact nature of your individual myeloma, your overall health and any complications that may arise. For example, about 40% of patients in England live for at least 5 years, and between 15-19% will live for at least 10 years.

The development of new drugs for the treatment of myeloma has meant that it is often seen by medical professionals as a chronic, yet lifelong, disease that people survive.